A Unique Geospectral Signature

An Economic Development & Political Economy Approach to Satellite Imagery and the Economic Landscape with Jeffry Frieden, Noted Author & Professor at Columbia University

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then satellite imagery may be worth an entire economic theory.

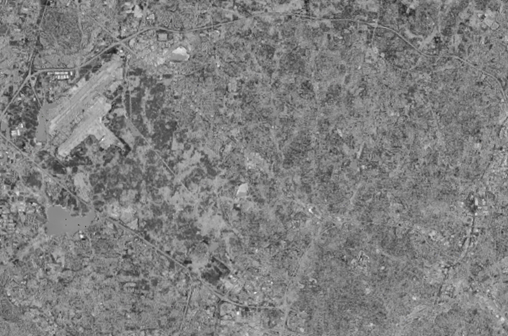

In “A Picture Is Worth a Thousand Words, Part II,” Atlas Analytics introduced a novel finding: every place has a unique Geospectral Signature.

As we wrote:

Our working hypothesis is that each geography blends its built environment, land use, and vegetative patterns differently, producing distinct spectral signatures that map onto local economic structures.

Today, in collaboration with Columbia University Professor and noted author, Jeffry Frieden, we explore the broader implications of this insight across two foundational domains: economic development and political economy.

Specifically, we ask how economic geography—long understood qualitatively—can now be observed, measured, and modeled quantitatively:

Why do some communities grow rapidly while others stagnate or decline? To what extent are these outcomes shaped by physical, infrastructural, and vegetative endowments?

Which policies foster durable growth—and which impede it? Can satellite-derived geospectral signatures help predict where specific policies are likely to be effective?

How do different communities express their unique geospectral signatures, and can these patterns help explain persistent political divides—such as rural conservatism and urban liberalism?

Does the concept of a geospectral signature offer a plausible framework for understanding the rise of populism in the United States and the secular decline in global trade integration?

We do not claim to have definitive answers to these questions. Instead, we aim to open a new aperture for economic inquiry—one that allows political economy and development to be studied through a spatial, empirical, and satellite-based lens—and to propose promising avenues for future research.

Economic Geography Meets Economic Development

From venerable institutions like the World Bank and IMF to research networks such as J-PAL and local development practitioners, one central question has long animated the field of economic development: what actually moves the needle for place-based growth?

The uncomfortable—but widely acknowledged—answer is that there is no settled consensus.

A rich array of theories exists, yet academic “best practices” often reflect what is empirically fashionable rather than what proves robust across time and place. Dig deeper, and the contradictions become clear. Many policy prescriptions directly conflict with one another. The Washington Consensus of the late twentieth century emphasized trade liberalization and minimal state intervention—just as earlier East Asian success stories such as South Korea and Taiwan pursued protectionist, state-led industrial strategies to foster domestic manufacturing. China’s subsequent rise followed a similarly heterodox path, blending global openness with extensive industrial policy.

The result is a development canon rich in insight, but fragmented in guidance.

So what, if anything, can satellite imagery add?

We do not yet claim to have the answer. But we believe we have a credible way to arrive at one.

Using satellite data spanning more than fifty years, Atlas Analytics has identified persistent spatial patterns that both explain historical growth trajectories and enable real-time GDP nowcasting. These patterns reflect how each geography uniquely combines its built environment, land use, infrastructure, and vegetation—what we call its geospectral signature.

This raises a natural question: what if, instead of using satellite imagery solely to predict future growth, we used it to infer which policies worked in the past—and where?

A region’s economic growth depends powerfully on its endowments: the physical characteristics of the land and its resources, along with what humans have created upon those characteristics. This helps explain what our research suggests: regions with similar geospectral signatures often exhibit similar growth dynamics. Geographic units with comparable physical and ecological characteristics often share similar economic and even policy outcomes. Policies that contribute to sustained growth in Benin may be more likely of success in Lesotho—a country we hypothesize has a similar geospectral signature. Conversely, policies that fail to generate physical and economic expansion in one region should be treated with caution when applied to geospatially analogous contexts.

To be sure, endowments are not everything. But they affect powerfully the interests of the people that inhabit a space, and the economic and political institutions those people create.

This approach does not promise a universal development blueprint. But it does offer a systematic, empirical framework for narrowing the policy space—grounded not in ideology or fashion, but in observed physical and economic reality.

This is the direction Jeff and I believe economic development research should move—and it forms the conceptual foundation for Atlas Analytics’ own consulting and advisory work.

The Political Economy of Place

Geospectral signatures may also help explain why politics and policies diverge sharply across space. Political economy, at its core, is concerned with how material interests shape political behavior. A central insight of Jeff’s work on trade and globalization is that political cleavages are not ideological accidents, but the outcome of uneven economic developments—developments that are deeply place-based1. Individuals and communities form political preferences through their lived economic experience, which depends fundamentally on the local environment. The local resource base, the local infrastructure, the local industrial structure – these have a profound impact on the risks they face, and the degree to which they benefit—or suffer—from economic integration.

Geospectral signatures provide a way to observe these local environments directly. Satellite imagery captures the physical imprint of economic structure: dense urban agglomerations anchored in services and knowledge industries; logistics corridors tied to global trade; land-intensive rural regions reliant on agriculture, raw material extraction, or legacy manufacturing. These spatial configurations map the distributional logic emphasized in Jeff’s analysis of trade politics. Regions characterized by diversified, globally connected economic networks tend to favor openness, state capacity, and redistribution. By contrast, regions characterized by concentrated, immobile, or declining economic activities often prefer protection, are skeptical of centralized institutions, and resist further integration. The familiar urban–rural political divide, in this view, is not merely cultural—it is spatially and materially grounded.

This perspective helps clarify the political backlash against globalization. It is well known that the turn toward populism is highly geographically concentrated in declining industrial areas: the North of England, northern France, eastern Germany, the American Industrial Belt. Jeff has argued that populism’s appeal in these areas is the result both of industrial decline – due to globalization and technological change – and of the failure of political and economic institutions to manage adjustment costs2. Geospectral signatures allow us to sharpen that claim. Regions with rigid physical infrastructures and limited capacity to adapt—what we might call geospectral lock-in—are more vulnerable to trade shocks and technological change, and thus more likely to experience political backlash when adjustment fails. By contrast, regions whose geospectral signatures evolve over time—through new infrastructure, land use transformation, or industrial diversification—appear better able to absorb shocks without destabilizing political consequences.

Critically, this framework does not imply political determinism. Institutions, politics, parties, and policies still matter enormously. But geospectral analysis makes the economic foundations of political conflict visible in physical space, offering a powerful complement to traditional political economy. Moreover, it points toward a constructive path forward. The same satellite-based insights used to understand why development succeeds or fails can inform how societies might reduce political polarization: by targeting investment, infrastructure, and industrial policy to help lagging regions adapt rather than stagnate. Economic development and political economy are two components of the same spatial reality—and satellites may help us see how to address it.

In Lieu of A Conclusion

This article does not end with a conventional conclusion, but with an invitation. Our aim has not been to offer a new grand theory of growth or politics, nor to claim that satellite imagery alone can resolve longstanding debates in economic development and political economy. Rather, we have sought to open a new aperture—one that allows the physical organization of place to be observed, measured, and analyzed alongside institutions, policies, and preferences.

By making economic geography visible at scale and over time, geospectral signatures offer a way to ground theories of development and political behavior in empirical reality. They provide a common language through which scholars, policymakers, and practitioners can better understand why similar policies produce divergent outcomes across space, why economic shocks generate political backlash in some regions but not others, and why adaptation succeeds in some places while stagnation persists in others.

The promise of this approach lies not in determinism, but in diagnosis. If we can see how economies and communities are structured in physical space—and how those structures evolve—we can design policies that are better matched to local conditions, more resilient to shocks, and more attentive to the political consequences of economic change. In this sense, economic development and political economy are inseparable: both are fundamentally about place.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then satellite imagery may help us see—more clearly than before—how place, politics, and prosperity are bound together, and how they might yet be realigned.

Jeffry Frieden is Professor of International and Public Affairs and Political Science at Columbia University, and Professor of Government emeritus at Harvard University. He specializes in the politics of international economic relations. Frieden is the author of Global Capitalism: Its Fall and Rise in the Twentieth Century and its Stumbles in the Twenty First (2006, second edition 2020); Currency Politics: The Political Economy of Exchange Rate Policy (2016); and (with Menzie Chinn) of Lost Decades: The Making of America’s Debt Crisis and the Long Recovery (2011). Frieden is also the author of Banking on the World: The Politics of American International Finance (1987), of Debt, Development, and Democracy: Modern Political Economy and Latin America, 1965‑1985 (1991), and is the co-author or co-editor of over a dozen other books on related topics. His articles on the politics of international economic issues have appeared in a wide variety of scholarly and general-interest publications.

View Jeffry Frieden’s website and list of publications here.